Due to the complexity of criminal procedures and the risk of conviction, you are strongly recommended to appoint a lawyer to represent you.

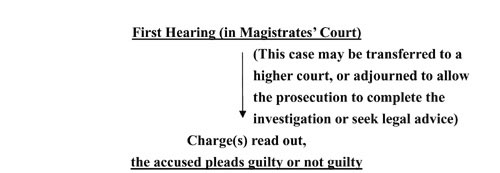

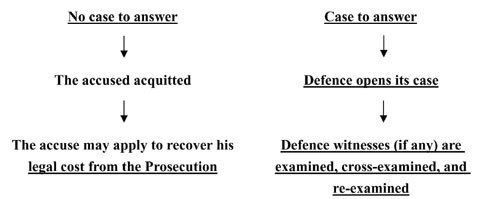

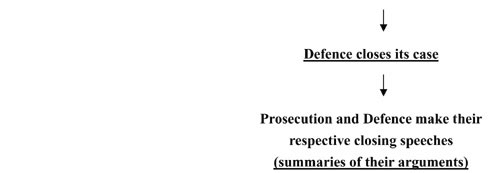

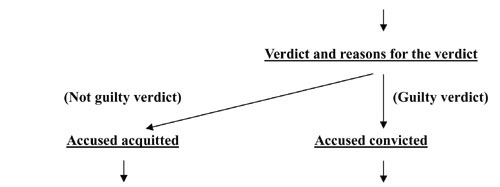

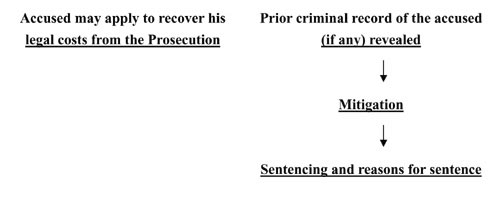

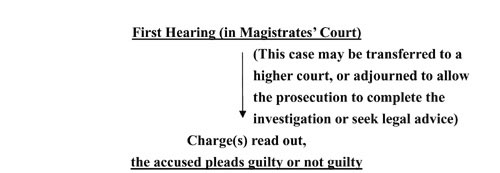

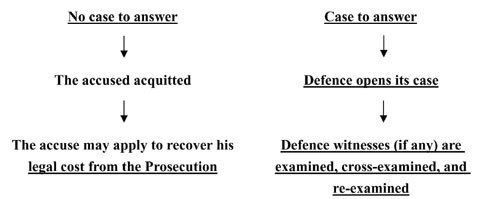

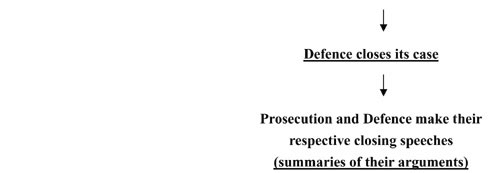

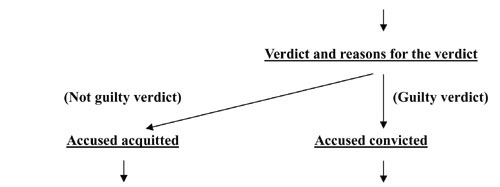

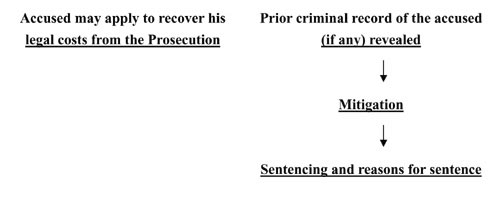

The following chart briefly sets out normal court procedure in a criminal case:

First Hearing

No matter how serious the offence is, the accused person will in general be brought to a Magistrates’ Court to attend the first hearing. If the prosecution needs further time to investigate or seek legal advice, or if the prosecution decides to transfer the case for trial in the District Court or the Court of First Instance of the High Court, then the prosecutor will seek an adjournment (to postpone the hearing). Otherwise, the charge is read to the accused person at the first hearing, who is then asked to plead guilty or not guilty to the offence. If the accused person pleads not guilty, then the case will usually be adjourned to another date for trial.

Upon adjournment of the case, the accused person may apply to the Magistrate for bail. Bail should generally be granted by the Magistrate unless there is substantial ground for believing that the accused will fail to appear at the next scheduled hearing, or commit other offences whilst on bail, or interfere with witnesses or the investigation. The accused person has the right to submit an application for bail on further appearances before the Magistrate if bail was refused at the previous hearing(s). He may also apply to the Court of First Instance of the High Court for bail upon refusal by the Magistrate. For more details on this matter, please refer to section 9Dand section 9G of the Criminal Procedure Ordinance.

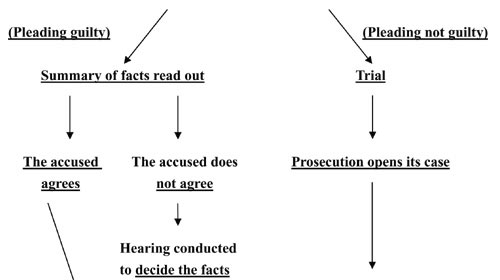

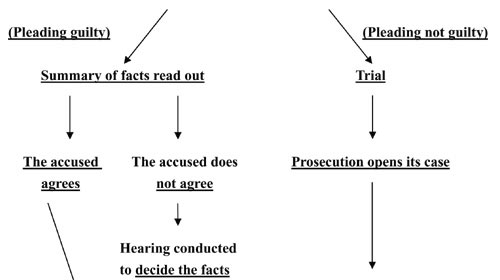

Plea of Guilty (the accused admits guilt)

The accused person who pleads guilty is not yet convicted of the offence until he is formally convicted by the Court. On a plea of guilty, the brief facts of the case on which the accused is to be convicted will be read in open court. If the accused agrees with the brief facts, then the Court will formally convict him (unless the Court is not satisfied that the agreed brief facts show the commission of the offence). Where the accused does not agree with the prosecution's brief facts (or part of them), the Court will hear evidence from the prosecution and the accused to decide the facts. Such a hearing is called a “Newton Hearing”. After the Court has made a decision on the facts, it will formally convict the accused (unless the Court is not satisfied that the decided facts show the commission of the offence).

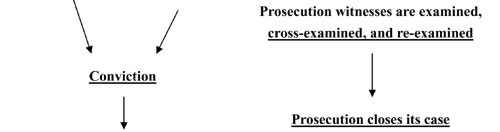

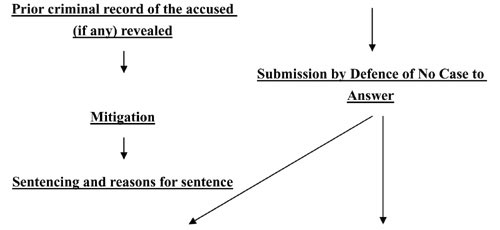

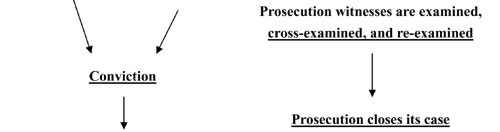

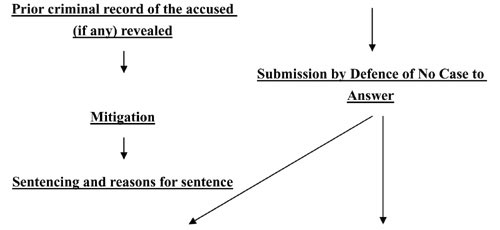

Upon conviction, the prosecution will inform the Court the relevant background of the accused person in particular whether he has any previous criminal records. The Court will then allow the accused person or his lawyer to tell the Court matters which may persuade the Court to impose a more lenient sentence. This process is called a plea in mitigation . The Court may then pass a sentence (i.e. decide the penalty) on the accused person or it may call for some reports (e.g. probation report, Community Service Order report or psychiatric report etc) before it decides the proper sentence.

Plea of Not Guilty (the accused does not admit guilt)

On a plea of not guilty, the case will be adjourned for trial. A number of procedures may take place before the trial e.g. for application for bail, for amendment to the charge, pre-trial review, etc.

Well in advance of the trial, the prosecution must provide the accused person (or his lawyer) with all documents and materials which are or possibly relevant to the case, whether they are for or against the prosecution's case. In general, these materials include all the written statements and criminal records of the prosecution witnesses; all written statements given by other persons to the law enforcement agencies whom the prosecution does not intend to call as a witness at the trial; all materials which the prosecution intends to rely on at the trial; and all materials which the prosecution does not intend to use but which may assist the accused in his defence. The prosecution however has no duty to disclose materials which only affect the credibility of a defence witness (e.g. Immigration records which show that a defence witness was in Macau at the time when he said he met the accused person in Hong Kong). Any failure by the prosecution to provide the accused with the relevant materials before trial may be a valid ground of appeal against any conviction.

Trial

The prosecution opens its case and adduces/submits evidence. The prosecutor will call witnesses one by one to give evidence to establish the offence. Each witness will first be questioned by the prosecutor (examination-in-chief by the prosecution). The witness will then be questioned by the accused or his lawyer (cross-examination by the defence). If necessary, that witness may be re-examined by the prosecutor afterwards. After all the prosecution witnesses have given evidence, the prosecution closes its case.

The defence may then make a submission of "no case to answer" , which is an argument that the prosecution's evidence is insufficient to make out a prima facie case. If this submission is accepted by the Court, the accused is acquitted . The accused may then apply to the Court to recover his legal costs from the prosecution.

If the Court finds that there is a "case to answer" (i.e. the prosecutor has established a prima facie case), the defence will open its case and call its witnesses. The accused can:

a) give evidence personally and call other witnesses;

b) choose not to give evidence personally but only call other witnesses to give evidence; OR

c) choose to do neither of the above.

The accused person usually needs to decide whether or not to give evidence personally before any defence witness is called. This is because the accused is generally required to testify before other defence witnesses.

Where witnesses are called by the defence, the defence witnesses are examined in chief by the defence. They may then be cross-examined by the prosecution, and may be re-examined by the defence. After all the defence witnesses have given their evidence, the defence closes its case.

Other than those witnesses called by the prosecution or the defence, the Court has the discretion to order that someone must be called as an additional witness. However, this discretion is rarely exercised.

Closing Submissions and Verdict

The trial will then proceed to the closing speeches by both the prosecution and the defence, (although the prosecution often does not make a closing speech) after which the Court will deliver its verdict (i.e. decision). The Court will either convict or acquit the accused and give reasons for its decision. In general, the reasons given by the Magistrate will be rather brief at this stage. The Magistrate will provide fuller reasons with more detailed analysis at a later stage if the accused appeals against the conviction. If the accused is acquitted, he may apply to the Court to recover his legal costs from the prosecution. If the accused is convicted, the case will proceed to mitigation and sentencing.

Hearings in District Court or Court of First Instance of the High Court

The trial process in the District Court is similar to that in the Magistrates' Courts. However, the trial in the Court of First Instance of the High Court is conducted by the Judge sitting together with the jury , and so there are some differences in the process. If the accused does not admit guilt, a jury will be empanelled. The members of the jury are ordinary citizens in Hong Kong selected by lottery from the jury pool. Both the prosecution and the defence may object to any member of the jury pool becoming empanelled as a juror. The defence can object to no more than five potential jurors without giving reasons and can object to any additional ones if valid reasons are given. Normally seven jurors are selected, although for long or complex trials a jury of nine members can be formed.

The trial then proceeds in similar manner as in the Magistrates' Court or District Court. The jury is responsible for deciding whether or not the accused person is guilty , while the Judge determines the law and procedures. Hence, the Judge of the Court of First Instance will regulate the conduct of the trial procedures and the jury will general sit there listening attentively to the evidence given by the witnesses (through examination-in-chief, cross-examination, and re-examination conducted by the prosecution and the defence). Sometimes the Judge will ask the jury to leave the courtroom if there are any legal issues or arguments that need to be resolved without the present of the jury (e.g. whether the jury should be allowed to hear certain evidence, or whether the defence's submission of no case to answer is successful).

After closing speeches have been made to the jury by the prosecution and the defence, the Judge will sum up the case to the jury (summarising the evidence and the arguments made by both sides). The Judge will usually explain to the jury what the prosecution must establish before the accused can be convicted. But in general the Judge must leave it for the jury to decide who is telling the truth and whether the accused is guilty of the offence. In certain exceptional cases, the Judge may direct the jury to acquit the accused if he is satisfied that it is not safe to convict the accused based on the available evidence.

The jury will then retire to consider its verdict (i.e. to decide whether or not the accused is guilty of the offence). Based on the verdict of the jury, the Judge will formally convict or acquit the accused. If the accused is acquitted, he may apply to the Court to recover his legal costs from the prosecution. If the accused is convicted, the case will proceed to mitigation and sentencing. It is the Judge instead of the jury who is responsible for sentencing the convicted offender.