5. What may happen during a civil trial? What is the usual procedure that the plaintiff and the defendant need to follow at the trial?

Both parties should attend court punctually on the trial date, bringing the relevant original documents and photocopies for the judge and for the other party if necessary. Your witnesses should come with you. The ground floor lobby notice board will show which court is hearing your case.

At the trial, the court will hear the evidence of witnesses and the submissions (arguments) of the parties involved. The court may adjourn the case to another date if further information and/or evidence is needed. The court may deliver judgment at the end of the trial or deliver/hand down the judgment at a later date.

Due to the complexity of the civil court procedure, you are recommended to appoint a lawyer to represent you.

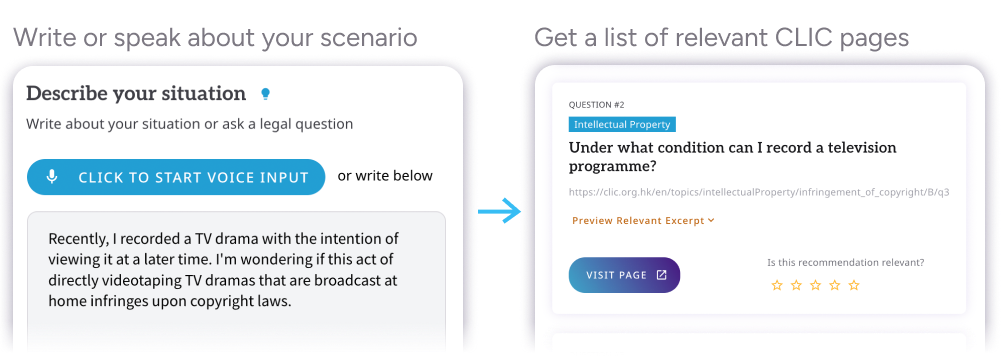

The following chart shows the ordinary course of a civil trial:

|

(A) The plaintiff's opening speech

|

|

(B) Plaintiff's witnesses will in turn be:

(i) examined in chief by the plaintiff;

(ii) cross-examined by the defendant; and

(iii) re-examined by the plaintiff

(After all the plaintiff's witnesses have given evidence, the plaintiff will close his case)

|

|

(C) The defendant's opening speech (if any)

|

|

(D) Defendant's witnesses will in turn be:

(i) examined in chief by the defendant;

(ii) cross-examined by the plaintiff; and

(iii) re-examined by the defendant

(After all the defence witnesses have given evidence, the defendant will close his case)

|

|

(E) The defendant's closing speech

|

|

(F) The plaintiff's closing speech

|

Explanatory notes:

A. The plaintiff has the right to begin by making an opening speech. The object of an opening speech is to give the court a general introduction of the dispute (e.g. the facts, the issues and questions to be determined, etc). In this opening speech, the plaintiff may state the substance of the evidence he is going to give and its effect on proving the case. The plaintiff may also point to the strength of his case and the weakness of the defendant's case. (NB In a simple case, the trial judge may give directions dispensing with the plaintiff's opening speech.)

B. After the plaintiff has opened the case, he will call his witnesses to give evidence. If the plaintiff intends to give evidence at the trial personally, it is customary that he is the first one to go into the witness box.

Each witness will take the oath or make a solemn affirmation, and is followed by:

Examination-in-chief: The plaintiff should start with questions as to the witness's name, address, relationship to the parties or the proceedings and, if an expert witness, qualifications. After that, the plaintiff should ask questions, which are relevant to the case facts.

Where a witness statement made by this witness has previously been disclosed to the defendant, the plaintiff should show a copy of that document to this witness, get that witness to confirm that it is his statement, and later ask the judge if the statement may stand as the evidence of this witness in this case.

The plaintiff should bear in mind that, as a general rule, he cannot ask his witness leading questions on disputed matters.

Cross-examination: The defendant will ask the same witness a series of questions to try to destroy or discredit the evidence given by this witness. When planning the questions for cross-examination, the defendant should identify the aspects of the witness's evidence which are most vulnerable to attack.

Generally speaking, the weaknesses which the witness may have are ambiguity, insincerity, faulty perception and erroneous memory. It is important to note that: (i) leading questions are allowed to be asked in cross-examination; and (ii) a failure to challenge evidence given in the examination-in-chief implies acceptance of it (but you should try to avoid asking trivial/tedious questions in order to show your objection).

Re-examination: The plaintiff can use the re-examination to restore his witness's credibility. The plaintiff can also try to use re-examination to allow his witness to explain points made in cross-examination which seem adverse to his case but in fact are not. However, re-examination must be confined to matters arising out of the cross-examination.

After all the plaintiff's witnesses have given evidence, the plaintiff will close his case.

C. If the defendant chooses to give evidence, he is entitled to open his case. However, in most cases, the defendant proceeds to call his witnesses without making an opening speech.

(NB If the defendant chooses not to give evidence personally and not to call any witness, the plaintiff may then make a second speech to close his case, i.e. to sum up his evidence and stress why the judge should find for him by referring to the relevant points of fact and law. On the conclusion of this speech, the defendant will make his speech in reply. The next stage would then be (G) below.)

D. The defendant calls his witnesses. If the defendant intends to give evidence personally, he is normally the first one to go into the witness box.

The defence witnesses will in turn be examined in chief by the defendant, cross-examined by the plaintiff, and re-examined by the defendant. The defendant should pay attention to what has been mentioned in (B) above.

After all the defence witnesses have given evidence, the defendant will close his case.

E. The defendant is entitled to make a closing speech. He should closely analyse all the witnesses' evidence and suggest why their evidence should be accepted or rejected. He may also advance arguments on the legal questions involved in the case with reference to the relevant authorities (including case precedents and ordinances). In that case, a lawyer would normally be in a better position to do the job.

F. After the defendant's closing speech, the plaintiff may make a speech in reply.

G. After the parties have made their closing speeches, the trial judge will either verbally deliver the judgment immediately or hand down the judgment in written form on a later date. In many cases, the party obtaining judgment (who wins the case) usually has its costs paid by the losing party.

Addressing the judge, the witnesses and your opponent

During the trial, you must address the judge as "Your Honour" (in the District Court) or "My Lord/My Lady" (in the High Court). You should also address the witnesses and your opponent as "Mr.", "Mrs." or "Miss". Do not use threatening or insulting words in the courtroom.

The above mentioned points are only the usual procedure for a trial. Depending on the circumstances, the judge may give other directions which you must follow.

Print

Print Email

Email